An Introduction To CLO Economics

What is CLO?

We could think of CLO rated-tranches (e.g. AAA to BB) as long-term non-recourse funding for a diverse portfolio of senior-secured non-investment grade corporate loans managed by a CLO manager. The first-loss unrated tranche is also known as CLO equity.

From the CLO equity standpoint, its return is driven by the long-term portfolio total investment return net of funding costs, including management fees, administrative fees and any costs relating to CLO reset or refinancing.

In a straight CLO refinancing, rated tranches would be refinanced at lower coupons. The refinancing cost-saving needs to more than offset the expenses involved in refinancing. Whereas in a reset, the reinvestment period of the deal would be extended.

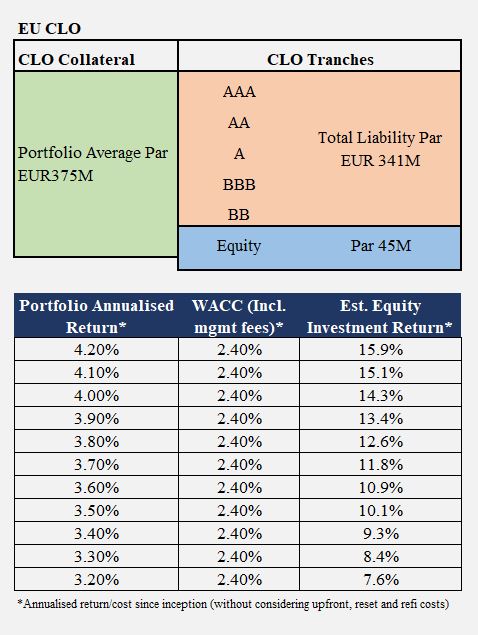

The diagram below shows the estimated economics of a sample EU CLO deal. This deal has done well (top tier performance) at the time of writing, registering a portfolio annualised total return of 3.9% since inception. Without considering any costs relating to upfront, refi and reset or increasing funding post reinvestment period, its corresponding estimated equity return would be at around 13.4%. As the diagram illustrates, the estimated equity return is sensitive to the actual portfolio total annualised return, given the leverage afforded by the CLO structure. Of course, This is a simplistic sensitivity model. It is trying to highlight the importance of portfolio total investment return (as shown in the table’s left column).

The initial upfront costs would explain the lower portfolio par as it does not add up to the sum of CLO rated liabilities and CLO equity par. For example, the portfolio par was EUR11M lower than the sum of CLO rated liabilities and CLO equity at the outset. This also means that the equity tranche principal par is lower than its notional at the outset in a regular CLO (e.g. around 80% instead of 100%).

How much is the portfolio net interest return needed to make the ‘arbitrage’ work?

The term ‘arbitrage’ is used in the CLO market frequently. Arbitrage may work if CLO portfolio credit spreads are greater than the weighted average cost of funding (including management fees) by a certain margin.

The portfolio total annualised return comes from both the interest and market value (MV) returns. So if the interest return is much higher than the cost of funding, more excess spreads flow through the waterfall structure (i.e. paying the rated tranches sequentially) and eventually getting to the equity investors. Having said that, the interest return of the portfolio is only one part of the total return equation. It makes a lot of difference if managers could also deliver a good underlying portfolio MV return.

Based on the 33 EU CLO deals closed in 2014, the average annualised interest return was 4.2%, and the average annualised MV return was -0.6% since inception. The total annualised return was at around 3.6% compared to the average 2.4% WACC (including management fees) as of mid-November.

It appears that a good starting point would be 1.8% of net portfolio interest return (including management fee but without taking into consideration upfront, reset or refinancing costs). 1.8% net portfolio interest return would provide a better safety margin than 1.5% (which is what the market thinks). At 1.5% (or less), there is probably not much room to absorb any portfolio credit losses over the deal’s life. The 30bp difference might sound like a small number, but given the typical 10x levered CLO structure, it would make a lot of difference to the CLO equity investors.

Potential credit losses could arise from trading and default over the life of the CLO deal. Credit losses due to trading could be even higher than losses due to defaulted assets. Managers could trade out distressed assets before they defaulted. Besides, most CLOs would be redeemed before their legal maturity dates and paper losses would be realised as a result. A CLO could only be redeemed if the portfolio’s liquidation value could well cover all the debt tranches.

To conclude, CLO equity arbitrage is driven by the overall portfolio returns instead of only portfolio interest return net of funding cost. Arbitrage is not only a measurement at issuance, but instead, one should perhaps monitor the actual ‘arbitrage’ performance picture constantly.

Disclaimers

The information, research, data, research related opinions, observations and estimates contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at by CLO Research Group, based upon sources believed to be reliable and accurate, and in good faith, but in each case without further investigation. None of CLO Research Group or its service providers; authorised personnel, or their directors make any expressed or implied presentation or warranty, nor do any of such persons accept any responsibility or liability as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness or correctness of such sources and the information, research, data, research related opinions, observations and estimates contained in this document. All information, research, data, research related opinions, observations and estimates contained in this document are in draft form as of the date of this document and remain subject to change and amendment without notice. Neither CLO Research Group nor any of their third-party providers shall be subject to any damages or liability for any errors, omissions, incompleteness or incorrectness of this document. This article is not and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell securities and shall not be relied upon as a promise or representation regarding the historical or current position or performance of any of the deals or issues mentioned in it.